On a recent Thursday, the Kraus House in Missouri, one of Frank Lloyd Wright’s last Usonian homes, was toured more than 1,700 times. The Martin House in Buffalo, New York, was toured more than 1,800 times. In the midst of the pandemic, Wright’s architecture was still drawing visitors (albeit via Instagram), proof that 61 years after the architect’s death, Wright’s work continues to fascinate and inspire. The continued importance was affirmed in 2019 when a group of eight of Wright’s buildings were added to the UNESCO World Heritage List, the first modern architectural designation in the United States. “Le Corbusier or Mies van der Rohe—they’re incredibly famous as architects,” says architect Lynnette Widder, who restored a home in Usonia built by Wright’s protogée Kaneji Domoto. “But they’re not necessarily famous as popular figures. There’s footage of Frank Lloyd Wright on 1950s game shows. [Wright was a mystery guest on What’s My Line? in 1956.] He was a larger-than-life figure.”

While Wright’s legacy remains strong, it takes scores of groups to keep it that way. Stuart Graff, the president and CEO of the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, estimates that there are about 75 organizations across the country devoted to Wright. The architect founded two of them himself, creating the Taliesin Fellowship, now the School of Architecture at Taliesin, in 1932, and the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation in 1940.

Taliesin West in Scottsdale, Arizona, is where Wright would spend the winter months.

The foundation is the largest Wright organization and operates two of the architects’ homes, Taliesin in Spring Green, Wisconsin, and Taliesin West in Scottsdale, Arizona, in addition to controlling the licensing of Wright’s intellectual property. Taliesin West drew 115,000 visitors last year and Taliesin had 25,000 visitors, according to the foundation’s annual report. “We’re trying to use the tour program to engage the public to think about this architecture of ideas and how can we live more in a more unified way with nature,” says Graff. “That’s the heart of Wright’s organic architecture, the seamless unity between the natural world, the built environment, and our lives.”

Taliesin West was Wright’s laboratory, so it seems fitting that the foundation’s preservation efforts lean on innovation. “When we do this preservation work, one of the things that we’re looking at is Wright’s legacy of advancing the field of architecture,” says Graff. “We are not doing our preservation work in a way that simply locks in a moment in time and tries to restore conditions as they existed.” This means experimenting with new materials, such as the fabric will that replace the acrylic roofs, an earlier experimental replacement of the original canvas roofs.

The Hollyhock House in East Hollywood, Los Angeles. It was added to the UNESCO World Heritage List in 2019.

When it comes to preserving other Wright-designed buildings, much of the work falls to individuals. “Wright has about 400 remaining buildings left and about two-thirds of them are private single-family homes,” says Barbara Gordon, executive director of the Frank Lloyd Wright Conservancy, an organization focused on preservation and stewardship of the architect’s built works and also helped spearhead the World Heritage List nomination.

The conservancy provides resources to building owners and public sites and advocates for at-risk buildings. Gordon says the organization is working to develop more online resources and bolster their advocacy work. “So much of preservation and protection is local,” she says. “And it really does come down to strong local ordinances. We lost a building in the early 2018, Lockridge Medical Clinic in Montana. There were no local protections for a building like that.”

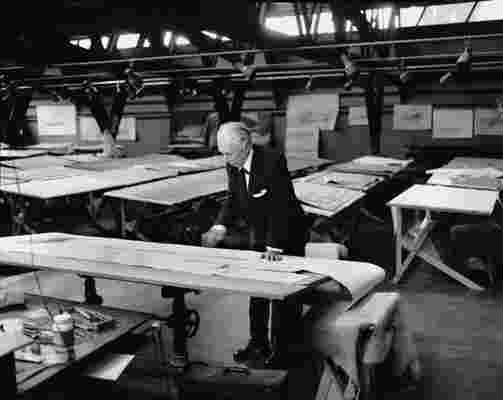

Wright at work in his studio.

While the AIA once called Wright the greatest American architect of all time, one area where his star does not shine quite so brightly is academia. “I’m very interested in his work, but very few other people that I know are,” says Neil Levine, author of The Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright and The Urbanism of Frank Lloyd Wright and a former Harvard professor. “I taught at Harvard for over 40 years and never had a graduate student who was interested in doing a dissertation on Wright.” Levine partially attributes this lack of interest to Wright himself. “He made fun of architecture schools,” says Levine. “He constantly criticized the establishment, especially what he called the ‘East Coast intellectual elite.’”

There was also the issue of access. “Those archives were in a no man’s land for younger scholars,” says Levine. The archives used to be held by the foundation in Arizona and Wisconsin, meaning scholars would have to travel to access the collection. (Levine recalls a student who was interested in doing a paper on Wright, but couldn’t visit Taliesin West because he wasn’t old enough to rent a car.) In 2012, the archives were acquired by Columbia University’s Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library and the Museum of Modern Art and moved to New York City, allowing for new research and scholarship around Wright’s work. “They will be seen by anyone who wants to see them, irrespective of how much they’re interested in Wright, or how much they’re interested in modern architecture and want to see things by Wright in relation to other things.”

Taliesin, sited in the Wisconsin River Valley, is the 37,000-square-foot home, studio, school, and 800-acre estate of Wright.

While research opportunities have increased, one education component of Wright’s legacy is in flux. On January 25, the board of School of Architecture at Taliesin voted to close at the end of the semester. The decision was the result of years of internal conflict between the school and the foundation, which have been separate entities since 2017, but have a Memorandum of Understanding, allowing the school to use the estates. The foundation declined to renew the MOU, which expires at the end of July, leaving the school without a home. However on March 5, the school announced that it had reversed its decision and would be working to find a way forward.

“It really came down to a question of whether the school would have a financially sustainable model to do its work,” says Graff. He added that the foundation would be creating its own higher education and professional programs, which they had been barred from having, due to a noncompete agreement with the school. “We had hoped to transform the relationship with the school, do some things differently with them,” says Graff. “That didn’t work out, so now we’re on separate courses.”

The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York City, completed in 1959, is considered one of Wright’s most iconic projects and remains one of the most noteworthy buildings in the U.S.

While the foundation is charting its new course, the school is still hoping that there can be a resolution. The parties recently participated in mediation, which was unsuccessful. According to Jon Kelley, an attorney at Kirkland & Ellis, which is representing the school pro bono, a number of positive developments have occurred for the school since the initial announcement, including the addition of new board members and the hiring of an interim president. “I think that the best outcome is to stop treating one another as enemies and rather work together to preserve the legacy of Frank Lloyd Wright,” says Kelley. “I am not sure that’s a realistic possibility, but I will say that the future is bright for the school because there are so many supporters and folks who have just come out of the woodwork to support the school, both financially and otherwise on an international basis.” He also added that the board is committed to making sure the school lasts with or without the foundation.

Wright at the Marin County Civic Center building site.

While tensions still appear high between these two bodies, other Wright organizations are finding new ways to work together. Graff notes that this new era of cooperation began three years ago during the 150th anniversary of Wright’s birth, and COVID-19 has brought the organizations together once again. Wright sites are swapping online tours on social media, bringing attention to smaller, less well-known sites, and sharing strategies for safely reopening. “I think that has really brought us together in a way that we probably wouldn’t have thought,” says Gordon. “Sometimes we all have our heads down and are trying to get our work done, so this has given us a great opportunity to look at partnerships a lot better.”

“Wright’s legacy is enormous,” says Graff. “And honestly, I think it is bigger than what a single organization can do on its own, especially in the nonprofit space. But when we all tell our parts of the story of Wright’s history and the role that each site plays in that history, we can together lift that legacy up and draw people in to see how relevant and important it is to today.”