Every Tom Kundig–designed project begins with a scribble. “Drawings, for me, are working tools,” says the architect. Like a writer’s shorthand, they may not be discernible without explanation from their creator, but they are “deeply informed, both by the context and some of the histories that I am bringing to the project.” Loosely to scale and driven by the intended program and specific client stipulations, those conceptual sketches have led Kundig through the nearly 45 years of practice celebrated in his new monograph, Working Title , out from Princeton Architectural Press on June 23. From commercial high-rises to wineries, from museums to private homes, the Seattle-based architect has seemingly done it all, translating the organic sensibility of his work for a variety of typologies with his AD100 firm Olson Kundig . The book allows an intimate look at these projects, including seven unpublished works, and his unique process of making architecture.

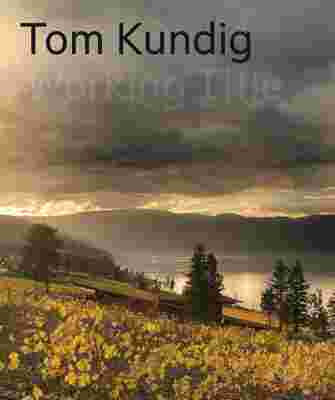

Working Title by Tom Kundig (Princeton Architectural Press, $80)

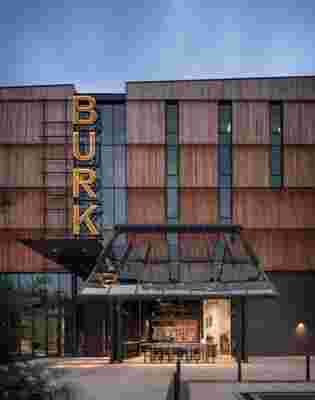

In addition to starting his conceptual sketches with developed design details, what sets Kundig apart is his ability to embed humanistic qualities into work of any scale. “Years ago, Glenn Murcutt [the Australian Pritzker Prize–winning architect] once said to me that residential architecture is the architecture that the architects have forgotten. In fact, residential architecture is the root and soul of everything we do,” he explains. Take, for example, the topography-hugging Martin’s Lane Winery in Canada, where an industrial interior is hidden by an intimate visitors’ entrance. Through a picture window in the cantilevered tasting room, guests become surrounded by the vineyards, and the Okanagan landscape beyond. Or see the new home for the Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture in Seattle. Though large and container-like inside, the museum’s shed roof is a nod to the traditional homes of the Coast Salish peoples, native to the Pacific Northwest. Though neither is a residential project, each incorporates home-like designs.

The new Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture, designed by Tom Kundig of Olson Kundig, has a pine façade on its upper floors and a roof shape inspired by the traditional homes of a First Nations people from the Pacific Northwest.

To Kundig, there is no distinction in the process to create projects of different typologies. “When you approach a large project or a small project, you are approaching it from the same basis: You are making a place for human beings to be human, which means that you have the same sort of value system that is working its way through these projects,” the architect says.

Martin’s Lane Winery in Canada was designed by architect Tom Kundig as two volumes, one that hugs the topography and the other that cantilevers over it.

The idea is guided by his close relationship with nature, one that began in childhood. Born in Northern California and raised in Washington state, he finds himself “nature-based in instinct,” and is excited by the utilization of natural materials in architecture, embracing the way they age and change over time. Residential projects like the three-story treehouse in Costa Rica, built entirely of local teak and passively operable, or Hale Lane on Hawaii’s Big Island, where interior and exterior are nearly indistinguishable, are prime examples.

An interior staircase in a Costa Rica treehouse, designed by Tom Kundig.

The treehouse was designed for clients who are both avid environmentalists and surfers.

But the architect’s love for designing with so-called “gizmos” (the levers, cranks, pivoting walls, wheels, and shades embedded in his work) is also rooted in the natural world. “When you move something large or heavy or cumbersome using the ideas of physics, you are embracing the natural world through your body,” he explains. And often, the movement of those large, heavy, or cumbersome things reveals a vista. Financier Kipp Nelson’s Hollywood aerie (revealed in AD ’s November 2019 issue and also featured in the new monograph) is a contemporary machine for living, where glass sliders open the living room to the pool, and mechanical shutters keep the evening chill out of a cantilevered master bedroom that seems to float over La La Land. Meanwhile, the previously unpublished Wasatch House in Salt Lake City is completely grounded, a series of three pavilions where landscape weaves in and under its sky bridges, and interior panels can open or close living spaces.

The Wasatch House in Salt Lake City, Utah, frames views of Mount Olympus.

“If you look through all the projects in the book, they are relatively narrow in certain directions to a sort of refuge area and then that refuge area can open to a big prospect view. So you’re always aware of the yin and yang of nature, both big views, refuge views; black and white; hard and soft; protected and exposed,” he says. “The intention is that you have your choice to either embrace, protect, or waive through use of these objects.”

A bedroom in a Dallas apartment.

While each of Kundig’s projects has their own contextual quirks, they all feel embedded in nature, whether they are actually urban or rural (the architect is currently completing a multi-family housing complex, 8899 Beverly Boulevard in Los Angeles, and several hospitality projects around the world). The thread that connects them all? Humanity, he says: “The basis is always what it means to be a human, what it means to be alive, what it means to experience our place and our short period of time on earth.”