Named an AD Innovator in 2013, architect Sou Fujimoto has captivated the world with his experimental projects. Born in Hokkaido, Japan, in 1971, he studied architecture at the University of Tokyo , then opened his own practice in 2000. Ever since, the trailblazer has made waves in both the public sector and the private, designing everything from London’s 2013 Serpentine Pavilion to unique residences around the world in his signature airy style. Fujimoto visited New York last month to talk about some of his favorite projects at the Japan Society. Here’s what he picked.

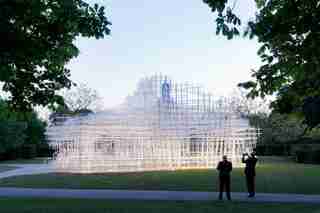

2013 Serpentine Pavilion, London

In his design for the annual installation in London’s Kensington Gardens, Fujimoto rejected some of the more traditional elements of a building (formal walls and a roof) in favor of more fluid, interactive modules that open the structure to the natural landscape. “This was an experimental project where I asked the questions, What are the elements of architecture? What are the elements of landscape?” said Fujimoto. “I wanted to redefine space in a new way.” The result was a combination of furniture and architecture, where visitors could choose to interact with the pavilion in a variety of ways: climbing on it, sitting on it, walking through it, or simply observing it, to name a few. “It went beyond the normal function of a building, allowing much more potential because [visitors] have more choice.”

Souk Mirage

Though never realized, Fujimoto’s entry to a competition to create a massive complex in the Middle East is a marvel. The design uses modular structures similar to the Serpentine Pavilion but enlarged to gargantuan size to house retail and office space, a cultural center, and plenty of public plazas shaded from the sun. “It was a nice challenge to expand concepts to huge scales. In the Middle East, anything is possible, so we could propose anything we’d like. We could expand imagination more than I expected!” said Fujimoto. “I still love the project, and I’m still looking for a client. That’s why I’m here tonight!” he joked.

Public Toilet, Ichihara, Japan

“A public toilet is an interesting thing for architects. It’s extremely public on the outside but extremely private on the inside,” said Fujimoto. He challenged all perceptions with this unique lavatory in Ichihara, Japan, in which the toilet sits in a glass room to offer the user unobstructed views of a garden. But don’t worry—privacy is offered by a black wall on the perimeter of the garden. When a nearby art fair brought hordes of tourists to the site, long queues formed to use the toilet. “The city government decided to put portable toilets along the wall,” said Fujimoto. “It’s the first time in history they built toilets for a toilet!”

Musashino Art University Museum & Library, Tokyo

“A library is a systematic space, but you should be able to wander, discover new books or ideas,” said Fujimoto. Taking this to heart, the architect sought to create a forest of books at the Musashino Art University, designing meandering rows of wood shelves. “It’s like a book heaven! But if you don’t like books, it’s a terrible space,” he laughed.

L’Arbre Blanc, Montpellier, France

For this residential project in the South of France, Fujimoto capitalized on the region’s excellent climate by extending the living spaces outdoors onto massive balconies. Though construction is in a very early phase, the units are completely sold out. “Even me, I can’t get one!” he said.

House of Hungarian Music, Liget Budapest, Budapest

Fujimoto was one of three architects selected to construct part of a museum complex in Budapest’s City Park. “It’s a 100-year-old park. What’s the ideal situation to play music [in it]?” asked Fujimoto. “At first, the forest itself is perfect, but we had to translate this into architecture.” The result is a transparent, airy space that blurs the lines between indoors and out.

Mille Arbres, Paris

Collaborating with Manal Rachdi Oxo Architectes, Fujimoto has designed a floating green village that will rise in Paris’s 17th arrondissement. The mixed-use project would see the growth of hundreds, if not a thousand trees (hence its name) just above the standard level of Parisian rooftops. “I think this could be the first Paris landmark to be made by nature,” said Fujimoto.