Bryan Stevenson, founder of the Alabama-based Equal Justice Initiative (EJI), has long demonstrated the power of language—as a civil rights litigator and the author of the best-selling 2014 memoir Just Mercy. But in 2013, Stevenson says, when EJI erected physical markers to the Montgomery slave trade, he was “blown away by their impactfulness.” So after the nonprofit organization issued a report on lynchings, in 2015, Stevenson and his colleagues set out to recognize that bleakest of American tragedies in more than mere words. That year EJI acquired six acres close to downtown Montgomery on which to build a centralized memorial to the 4,400-plus victims of lynching.

Unveiled on April 26, EJI’s National Memorial for Peace and Justice now stands as a sobering reminder of racial inequality in America, from slavery to segregation to mass incarceration. The centerpiece is a group of 800 pillars that, from a distance, appear to be holding up a roof, Parthenon-style. Get closer and the columns are revealed to be suspended from above, rather than supported from below. Hanging, they represent the casualties of lynching, which occurred in some 800 counties from 1877 to 1950. (Each column bears the name of a county and its known victims.) The slabs are made of Corten steel, a material that will rust indefinitely. “Every piece has blemishes and streaks that will evolve in terms of color and complexion,” says Stevenson. In the park around the central memorial are 800 duplicate pillars, waiting to be adopted by their respective counties. Over time, absences will reveal which communities have helped spread the memorial’s moving message—and which have not.

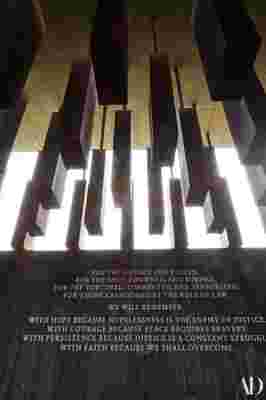

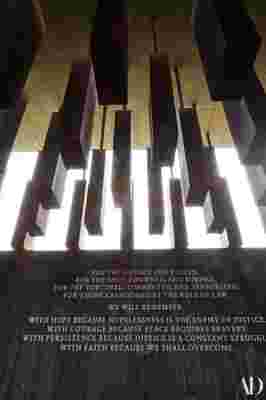

An inscription by The Equal Justice Initiative.

The building that contains the hanging columns was conceived in collaboration with Michael Murphy of MASS Design Group, a Boston-based architecture firm best known for its public-interest projects in Africa and Haiti. In his 2016 TED Talk, viewed more than 1.3 million times, Murphy says that he read about EJI’s mission and was inspired to email Stevenson. Soon he was on a plane to Montgomery. “Murphy is an incredibly talented architect,” says Stevenson, who nonetheless took care to ensure that visitors “look beyond the architecture to the larger story.”

Indeed, as the scope of the project expanded, EJI consulted writers like Toni Morrison and enlisted artists like Hank Willis Thomas, who conceived a sculpture inspired by police violence, and Dana King, who created statues dedicated to the women who carried out the yearlong Montgomery bus boycott (1955–1956). And a few blocks from the memorial, the organization added the Legacy Museum, in a renovated building on the grounds of a former slave warehouse. Taken together, the museum and the memorial cover the sweep of racial injustice in the United States and offer a place, Stevenson says, for all Americans to “confront our history.”