View Slideshow

Around 1900 several of the great Paris decorating firms, such as Allard et ses Fils and Alavoine, began to expand their operations, establishing showrooms in the Americas in the hope of attracting new clients eager to add a veneer of sophisticated French taste to their already opulently gilded lifestyles. Few of them, however, equaled the energy and ambition of the House of Jansen, which opened offices not only in New York but also in Buenos Aires, Rio de Janeiro and Havana.

The business was founded in Paris in 1880 by Henri Jansen, who, although Dutch by birth, had made himself a prominent figure in the Paris worlds of antiques dealing and furniture making, and in that curious gray area that lies somewhere between. Progressing naturally to the creation of complete rooms and the decoration of whole houses, Jansen specialized in solidly grand, if rather vague, "tous les Louis" period–style work. He rapidly outdistanced his rivals in amassing a superb stock of furniture as well as exquisite French boiseries and entire rooms of carved woodwork from important houses across Europe—for example, the Hotel Parr in Vienna. Then, momentously, in 1923 Jansen was joined by Stéphane Boudin, who within little more than a decade would become one of the era's most celebrated decorators and make the name Jansen a byword for grandeur and chic.

Boudin was born in 1888, the son of a passementerie manufacturer who was a major supplier of tassels and trim for Jansen. He rose quickly to be the firm's principal designer and was soon working for prestigious clients, such as the Prince of Wales (later duke of Windsor), for whose country retreat Fort Belvedere he laid out stylish, comfortable interiors. As the thirties began he was doing several projects in France, but most were in England.

He had a formative influence on the making of the grandiose interiors at Ditchley Park, the home of Nancy Astor's niece Nancy Lancaster, who later took up decoration herself, becoming the partner of John Fowler. Coming from widely differing traditions, Lancaster and Boudin agreed completely on the subtle painting of old woodwork. "He had the most extraordinary good taste," she said, "and understood color."

Boudin was "the greatest decorator in the world," according to Sir Henry "Chips" Channon, the American millionaire socialite who settled himself at the very heart of the English political establishment. For him Boudin designed in 1934 the most frivolous room of the era, and one of the most expensive—a rococo fantasy based on the riotous pale-blue-and-silver Amalienburg Pavilion of the Nymphenburg Palace, near Munich. Installing a mirrored table and thirty rococo chairs and side tables inspired by furniture from the Hotel Parr, Boudin charged his client a cool six thousand pounds, which would be approximately half a million dollars today. Ironically, wartime bomb damage revealed that much of the decoration was not the carved wood Channon imagined but cast plaster.

His 1938 commission to design a tented pavilion for a party for Elsie de Wolfe earned Boudin the sobriquet the "decorator's decorator." He went on to do extensive work for the duke and duchess of Windsor: first in their Paris house; then, after the war, at their country place, the Moulin de la Tuilerie (famously damned by Billy Baldwin as revealing Wallis Simpson's "tacky" southern taste); and culminating in their house in the Bois de Boulogne. Neatly judging the ambiguous semi-royal status of the place, Boudin invented effects that somehow hinted at both Buckingham Palace and Miami. The drawing room, with boiseries carved with rope tassels, was inspired by a Bavarian palace; the English wit John Cornforth likened it to "almost a smart restaurant."

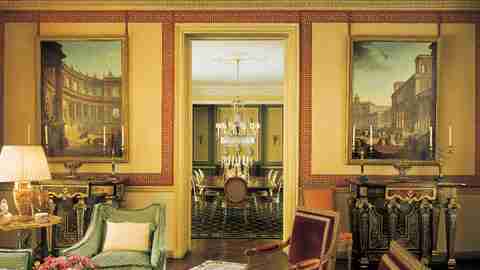

The fifties and sixties brought Boudin a stream of important commissions. He did residences for the Paleys, C. Z. Guest, H. J. Heinz and the Wrightsmans in the United States, and in Europe he designed sumptuous houses for the Agnellis and the king of Belgium. Much of this superb work remained discreetly unpublicized. By contrast, his involvement in the early-1960s redecoration of a number of rooms at the White House put him right in the public eye.

Chosen by a committee headed by the renowned collector Henry F. du Pont, Boudin found himself working closely with Jacqueline Kennedy. His arrangements emphasized the crucial role that French taste and furnishings had played in the decorations of the White House since Jefferson's day. Although perhaps for political reasons the role of Boudin (because he was a Frenchman) was minimized, the White House project nonetheless represented his finest hour.

Stéphane Boudin died in 1967, leaving the New York side of the business in the hands of Paul Manno, who had been with the firm since the thirties. Pierre Delbée continued to carry the torch in Paris. He was responsible for major projects, such as the spectacular library in the Madrid mansion of Bartolomé March and his own extraordinary residence, one of the last classic set pieces in the Jansen style; its contents were sold by Christie's in Monaco in December 1999.

Shortly after the sale of the business to new owners in 1979, the dynamic young design duo of Elisabeth Garouste and Mattia Bonetti were invited to set up installations of their weirdly innovative "Stone Age baroque" furniture in Jansen's august Louis XVI–style rooms. Sadly, this memorable show was the swan song of one of the last of the great Paris houses; in the late eighties, just over a century after its inception, the House of Jansen finally closed its doors.