View Slideshow

Richard Neutra, like many architects, had a great affinity for music. When asked late in his life which music he most identified with, which composers he would most want the users of his buildings to think of when they experienced his architecture, he replied without hesitation, "Schonberg and Bach." In musical and poetic terms he was evoking an image of his own work—the tension of contrasts working together, old and new, classical and modern. But what fell between those two extremes also shaped Neutra profoundly—the bittersweet world of European romanticism, from Beethoven and Brahms to Wagner and Mahler. And it was the music and ethos of those Germanic giants that permeated his youthful milieu in turn of the century Vienna.

All three epochs—classical, romantic, modern—would come to be expressed in Neutra's architecture, the first and third in the cool rationality of his machinelike designs, the second in the siting of his elegant structures amid the sensuous landscape of southern California. The contrasting, complementary moods informed his architectural and landscape drawings as well.

Some of the earliest works were pencil sketches from his wanderings in Italy as a student in 1913. The latest were pastels of Los Angeles houses from the early 1950s, by which time most of his firm's graphic work was being done by younger associates, with occasional "touch up surgery" by Neutra himself. The most dramatic examples were detailed perspectives aimed at "hooking" potential clients and convincing them that whatever the obstacles, their buildings had to be realized. Neutra also lavished attention on drawings slated for publication, knowing that such presentations would enhance his reputation and perhaps lead to future commissions. In all their forms, the drawings framed and reflected the architect's life and work.

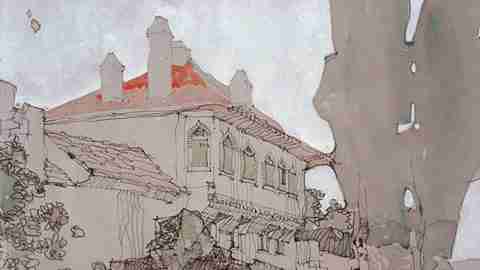

He was born on April 8, 1892, in Vienna, the son of an industrial metallurgist whose Jewish ancestry had been tempered by several generations of agnostic secularism. Neutra's older sister and brothers moved in sophisticated Viennese cultural circles, and through them he met Gustav Klimt, Arnold Schönberg and Sigmund Freud. Portraits and travel sketches from his student days through the darker years of World War I exhibit the Klimt and Schiele aesthetic. In his fantastical Portrait of a Horse (1915) and his series of architectural watercolors from Croatia and Bosnia-Herzegovina, he incorporated gold and silver paint in the Klimt manner. Pencil, charcoal and crayon landscapes from the teens and early 1920s show traces of both Klimt and Schiele, while several dark and brooding drawings from postwar Switzerland underscore the architect's depressed, almost suicidal view of his life.

In prewar Vienna Neutra was greatly impressed with the Secessionist architecture of Otto Wagner, but a more direct impact was made by Adolf Loos, whose crusade against ornament turned his mind away from historic styles and formulas. During World War I Neutra served as an artillery officer in the Balkans, but he returned to Vienna during the war to graduate cum laude from the Technische Hochschule.

Leaving Austria in 1919, he worked briefly in Switzerland for noted landscape architect Gustav Ammann, which influenced his later achievements as a site planner and landscaper. In 1920 he moved to northern Germany, where he served as the city architect of Luckenwalde, and a year later he joined the Berlin Expressionist architect Eric Mendelsohn as a draftsman and collaborator. Neutra's most noteworthy work in Mendelsohn's office was the Zehlendorf housing group in Berlin. A bold crayon drawing of a single house in the unit was done in the broad, thick strokes of the Mendelsohn style, but the bird's eye perspective of the whole composition presages Neutra's crisper American approach.

In 1923 the young architect immigrated to the United States, worked briefly in New York and then joined the large firm of Holabird and Roche in Chicago. There he met Louis H. Sullivan, who was dying in poverty and neglect, and at Sullivan's funeral he saw Frank Lloyd Wright, who invited him to work and study at Taliesin through the fall and winter of 1924. Neutra's most important drawings for Wright were of a proposed automobile observatory for Sugarloaf Mountain, Maryland (1924), whose curving forms both displayed the Mendelsohn influence and prefigured the Guggenheim Museum.

Yet by the time he met his idol, most of Wright's then-meager practice was centered in Los Angeles, and, attracted by the area's climate, landscape and architectural potential, Neutra decided to move there. He and his family rented an apartment in the modernist house of his Viennese friend Rudolph Schindler, who had also worked for Wright in Wisconsin and Los Angeles. The two expatriates formed a loose partnership, and in 1926 they entered the competition for the new League of Nations headquarters in Geneva, for which Neutra did most of the presentation drawings. At the same time, a group of apartment house designs for a Hollywood developer was realized in only one structure, the Jardinette Apartments (1927). Neutra's lyrical drawings of half a dozen even larger structures suggest what his future Hollywood might have looked like.

Among the handsomest drawings of the period were done for his unbuilt model metropolis, Rush City Reformed, where tall towers are relieved only occasionally by small drive in markets and low rise garden apartments. Yet the drawings for Rush City and the League of Nations buildings are eclipsed by those of the Lovell "Health" House (1927-29) in Los Angeles, which Neutra designed for physician Philip Lovell. It was, in fact, this spectacular building that brought the young architect international renown and led to his inclusion in the epochal 1932 "Modern Architecture" show at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

Indeed, Neutra's work of the 1930s, including several important commissions from film industry figures, epitomized what the MOMA show labeled the International Style—an architecture of elegantly spare, white, flat roofed pavilions with functional floor plans of interlocking, asymmetrical spaces. The building for Universal Pictures founder Carl Laemmle, at the corner of Hollywood and Vine, featured a restaurant and shops on the ground level with offices on the second floor, topped by large built in billboards advertising Universal's current releases. In the houses for actress Anna Sten (1934) and director Josef von Sternberg (1935) and writer producer director Albert Lewin (1938), curving lines punctuate the otherwise rectilinear geometries.

Neutra also achieved success in the 1930s and 1940s in the middleclass Strathmore, Landfair, Kelton and Elkay apartment complexes in Westwood, as well as in structures for people of modest means, such as the Channel Heights housing for shipyard workers at the Los Angeles harbor, San Pedro. Among his most poignant drawings of the era are unbuilt designs for dairy workers' cooperatives and for migrant agricultural laborers, the former utilizing recycled fruit packing crates.

Whereas Neutra's drawings of the 1920s were primarily done in pencil on tracing paper, the dominant medium of the 1930s was ink over pencil on sleek linen paper, which was more suitable for reproduction in publications. The 1940s saw a mixture of pencil and ink with the addition of pastels over brown or black line prints. In this way, Neutra colored his drawings more freely, without having to worry about spoiling the pencil or ink original.

The shortage of industrial materials during World War II led to wood buildings such as the Nesbitt House in Los Angeles (1942), and for the rest of his career Neutra alternated wood with concrete and natural stone. The Kaufmann House in Palm Springs (1946) recalled his style of the 1930s and showed the influence of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe's Barcelona Pavilion (1929). The Tremaine House in Montecito (1948) was an important transition to his more lyrical and relaxed designs of the 1950s and 1960s—houses that no longer seemed startlingly avant garde, but pleasantly suitable for popular magazines.

By 1949 Neutra was at the height of his career and appeared on the cover of Time . His newly formed partnership with architect Robert Alexander resulted in major urban commissions in Sacramento and Guam and such large public buildings as the United States Embassy in Pakistan (1959), the Lincoln Memorial Museum in Gettysburg (1961) and the Los Angeles County Hall of Records (1962). In the late 1950s the partnership was dissolved, and Neutra spent most of his last decade working with his son Dion. Their most notable effort was the redesign of the VDL Research House in Los Angeles (1965). From the 1930s through the 1960s, Neutra's office staff included a number of gifted architects, many of whom went on to prominent careers of their own. By the mid 1950s they were also doing a large part of the firm's drawings.

In 1968 Neutra was nominated for the Gold Medal by the American Institute of Architects with support from many of the world's greatest architects and critics. Kenzo Tange noted that he and his Japanese compatriots were drawn to the "exquisite sensitivity in his space and his delicate treatment for structures and materials." Walter Gropius wrote that Neutra "worked as a lonely pioneer designing modern buildings, the like of which were then unknown on the West Coast. Against very great odds," he added, "he stuck to his new artistic approach and by skill and stamina, he slowly achieved a true breakthrough." Mies van der Rohe believed that "architecture is the result of the threads of thought and activity of a handful of men who persevered in their efforts and maintained their ideals." Neutra's work, he emphasized, was "one of those threads. By his example," he continued, "he has influenced and taught a generation of architects, for whom the profession and the world is in his debt." Sybil Moholy Nagy argued, "The sum total of his buildings is much more important than judgment passed on the success or failure of individual solutions." She urged the AlA to give the award to Neutra, "if only to restore faith in its professional integrity."

But the AlA declined to honor the architect. Especially in his later years, his nervous arrogance had offended many of his peers, just as his later work had for some come to seem increasingly "old hat modern."

It would be another nine years before Neutra would win the Gold Medal—posthumously. The fact that he did receive it suggested that even in the heyday of Postmodernism, the world of architecture was ready for new historical appraisals. And in 1980 the Museum of Modern Art announced a Richard Neutra retrospective to open in 1982, the fiftieth anniversary of the "Modern Architecture" show that had given the architect his early acclaim.

Neutra became an American citizen in 1930, but in many ways he remained the awestruck immigrant. He believed fiercely in the promise of the American dream, but he was frequently puzzled and saddened by the nation's inert complacency, its penchant for self destruction and its persistent failure to realize its promise. In fact, Richard Neutra shared certain characteristics with E Scott Fitzgerald's Jay Gatsby, whose "dream must have seemed so close that he could hardly fail to grasp it. He did not know that it was already behind him somewhere back in that vast obscurity" Like Neutra, Gatsby believed in "the orgiastic future that year by year recedes before us. It eluded us then, but that's no matter—tomorrow we will run faster, stretch out our arms farther." And so, Fitzgerald concluded, "we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past."

Though the status and reputation of Neutra and his modernist generation were overshadowed in the 1960s and 1970s, writer Robert Ardrey offered Neutra a cogent assessment of his achievements:

There is probably no city in the world where the influence of your work and your ideas cannot be read in stone and stucco, realized by men you never met. This is the genuine immortality, when what a man has done so thoroughly imbues his time that it takes on a kind of anonymity.... I can remember times in Los Angeles in the '30s when there was only one man, Richard Neutra, and you said, 'That's a Neutra house.' Nobody else could have built it. And then later you looked at a house and you said: 'Look at the Neutra influence.' But then later on, unless you were a Neutra fan and connoisseur, you wouldn't say it because your concepts had spread so widely and deeply into domestic architecture that they had become part of the modern way of life.

Today, a little more than a hundred years after Neutra's birth, his work endures as a vital part of the architectural landscape.